The Pardessus de viole

Small viol with 6 strings is called a Pardessus de viole

The birth of the pardessus de viole

At the end of the 17th century, Italian music began to spread its way to France. The violin, the Italian instrument `par excellence` that was formerly despised for its connections with the lower, working class, began to see its days of glory much as a result of the works of Corelli, notably with the publication in 1701 in France of Corelli`s Opus 5.

It was previously thought the six string pardessus de viole developed sometime before 1701 as the first evidence is Jean Rousseau`s Will of 1699. However, the recent discovery of a Michel Collichon pardessus dated by the maker’s manuscript label to the year 1686, puts a much earlier date on the emergence of this instrument.

In 1686, Lully was still alive and at the peak of his powers, Marin Marais Premier Livre was published and De Machy’s Pièces de Violle en Musique et en Tablature (1685) had appeared the year before, while Jean Rousseau’s Traité de la Viole (1687) and Le Sieur Danoville’s L’Art de Toucher le Dessus et Basse de Violle (1687) would appear one year later. It would seem the pardessus was first created, not in some post-classical twilight of the French viol tradition, but at its absolute height.

In 1692 Marin Marais published Pièces en trio intended as musique de chambre, specially  crafted to delight the monarch with allusions to theatre music. It is in part suggested by his instruction, that his pieces would also sound well when played by two dessus de viole, (treble viols). However, some high passages could be played effortlessly on a par-dessus, given that the new tessitura allowed the performer to play up to d” in first position.

crafted to delight the monarch with allusions to theatre music. It is in part suggested by his instruction, that his pieces would also sound well when played by two dessus de viole, (treble viols). However, some high passages could be played effortlessly on a par-dessus, given that the new tessitura allowed the performer to play up to d” in first position.

The earliest documented tuning for the pardessus is given in Joseph Sauveur’s Principes d’acoustique et de musique of 1701, which gives the familiar g-c’-e’-a’-d”-g” tuning, also found in the Avertissement of Marc’s Suitte de Pièces and Corrette’s Méthode pour apprendre facilement à jouer du par-dessus de viole, 1748. As a natural development, a smaller body soon began to be built in order to serve this new tuning. The new viol, the pardessus de viole was popular among viol players who were fond of Italian music, but also, importantly, among a public of women. It was considered far more `decent` for a lady to have a pardessus de viole resting between the knees, than a violin on the arm.

Read more about the history of the pardessus de viole.

Virtuoso players in the 18th century

Read moreOnly two players achieved ‘virtuoso’ status on the pardessus with their performances in Paris during the 1740s and 1750s at the Concert Spirituel, causing quite an enormous stir. Madame Levi, a player from Rouen and possibly a pupil of Heudeline, performed no less than 12 times in 1745, with virtually all of her performances co-coinciding with motets by Lalande, and works by Blavet, Mondonville and Guignon, played by the composers themselves. What Madam Levi herself played isn’t known, but is seems unlikely that she would have performed her own compositions, rather adaptations of violin sonatas or concertos on the pardessus de viole.

Her playing quickly aroused unanimous praise throughout France, for people were amazed by the brilliance and technical virtuosity presumably unheard of before in public.

Michelle Corrette described her as ‘The Celebrity – Madam Levi’. Her sister Madam Haubault, was also a virtuoso pardessus player and performed at the Concert Spiritual during 1750 to 1762.

The most well-known performers of the pardessus de viole were undoubtedly the daughters of Louis XV to whom many of the works were dedicated.

Repertoire for the pardessus de viole

Read moreWhile over 250 publications from the 18th century mention the pardessus de viole as a performance possibility, only a small amount of music was written expressly for it. It was commonly used as a violin or flute substitute. However, in the case of pieces written expressly for the pardessus de viole we do sometimes see the opposite as with Barthélemy de Caix’s 6 Sonatas for Two Five-stringed Pardessus de Viole, Violins or Bass Viols, perhaps the most challenging pieces in the instrument’s repertoire and very similar to Leclair’s Sonatas for Two Unaccompanied Violins. Several other works by composers such as Charles Dollé and Pierre Hugard give the violin as a pardessus de viole substitute. The composer, Lendormy even wrote pieces for the pardessus de viole and violin to play in dialogue, though sadly these have been lost. The recent discovery of Boismortier’s Op 63 for two 6 string pardessus is an important find.

Up until the late 1760s there was a practice of playing transcriptions of Marais’s and Forqueray’s music as well as music by other composers such as Charles Dollé and Charles Henri de Blainville. In 1759, the composer Villeneuve published a selection from Marais’s Five books, Piece de Viole and on the title page writes;

Ajustées pour les pardessus a viol, a cinq cordes.

The change from viola da gamba to pardessus de viole

Read moreViola da gambists switched to the pardessus to enable them to continue playing the viol later into the 18 century as the violin family became more popular.

Ancelet, Observations sur la musique, les musiciens, et les instruments (Amsterdam,

1757).

“The bass viol is now confined to the apartments of the supporters of the old style of music, who, being entertained by it all their lives, seem to want to perpetuate their tastes and inspire their children and especially their daughters, for decency’s sake to prefer the pardessus to other instruments, as if it would be less respectable to place the violin on the shoulder than the pardessus between their knees”.

In a letter to Louis XV, Pierre-Louis d’Aquin gives an interesting insight:

– “the masters of the viol have sadly seen their instruments fall into disuse, but have had recourse in the 5 string pardessus de viole, a strategy that has succeeded, because we always need something new.”

Bowing the pardessus de viole overhand

Read moreThe last surviving method for the pardessus, written in 1765, is by C.R. Brijon (writing under the name Poseul de Verneaux). It mentions the ‘new’ method of bowing for the violin that places down-bow on strong beats. He suggested that the pardessus should be bowed overhand as the violoncello in order to remain competitive with the violin and not suffer the same fate as the bass viol, which lost popularity after 1740.

We cannot be sure if the over hand bow hold ever gained any popularity, but L’Abbé le fils tell us on the title page of his Principes du Violon that the under bow grip is still used as late as 1772 by his comment:

“People who play the pardessus de viole with four strings can use this method, observing only to give the letters t and p tirez (pull) and poussez (push) – the strong and weak bow directions respectively in overhand bowing, [but the opposite in underhand], an opposite meaning to that found in this book.”

The Guillotine for the pardessus de viole

Read moreLater, the 5 string pardessus shed another string and adopted a straight violin tuning, surviving more or less, until the French Revolution, in 1789 on a diet of violin music. By now, manners and tastes had changed in France and more and more women were beginning to take violin lessons, which in turn posed yet another threat to the pardessuss’s continued existence.

Nicolas Lendomry’s Second Livre de Pieces in 1780 was the last published music for the pardessus de viole.

19th & 20th century pardessus de viole

The pardessus de viole was revived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by English and French musicians and historians. At the time its historical use and repertoire were little known and many played it on the shoulder like a violin. This has led to a misconception which still continues, in some cases, to this day.

Cecile Dolmetsch was one of the first musicians to write about the instrument with an historical approach. Besides the Chantry Suite written by Christopher Wood there are few pieces in the 20th century which use the pardessus de viole. These include works by composers such as members of the Casadesus family, known for their historical concerts, and Ottorino Respighi who wrote a quartet.

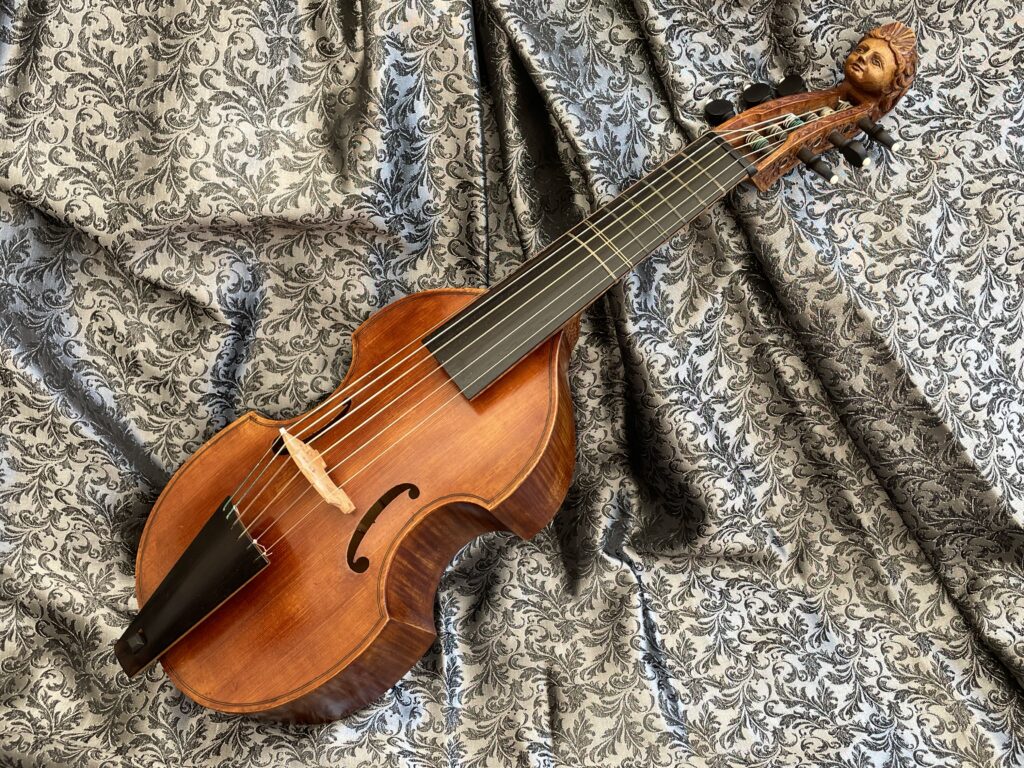

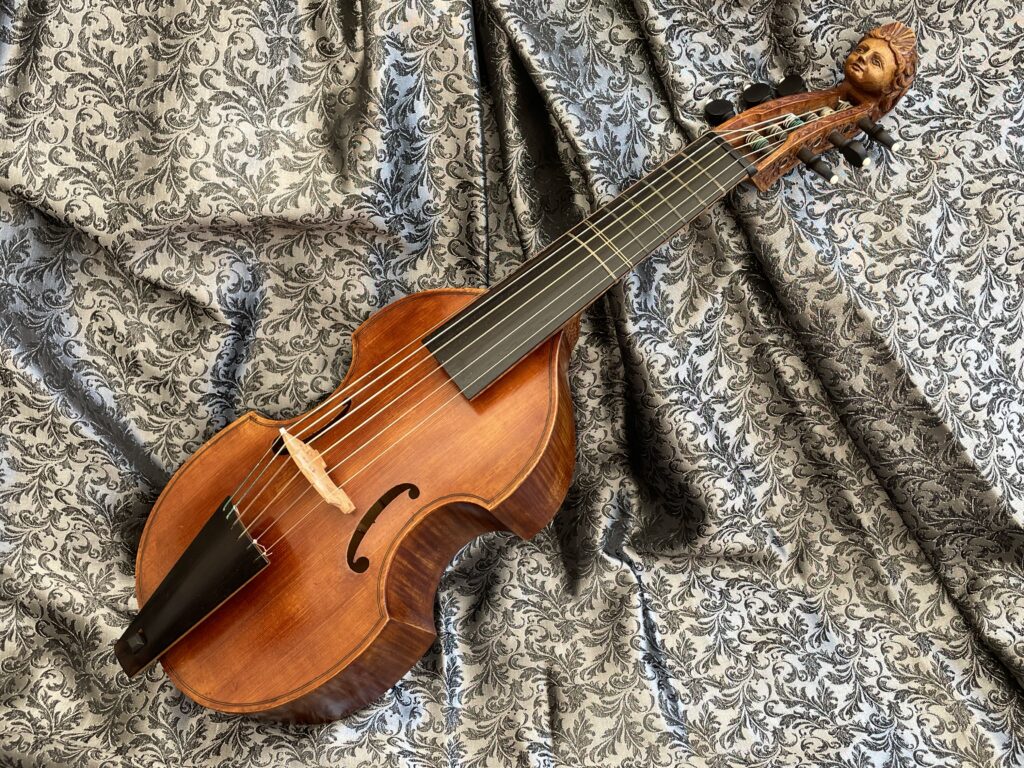

The Quinton

Small viol (shaped like a violin) with 5 strings is called a Quinton

The birth of the Quinton

The limited projection of the pardessus de viole became more evident after the opening in 1725 of the first French series of public concerts, the Concert Spirituel, in the spacious hall of the Palais des Tuileries.

So, the pardessus changed, incorporating features of the violin and around 1725 a new sort of viol began to be built in France, sharing the features of the violin family.

- F shaped sound holes

- Pointed corners

- Overlapping edges of the table and back

- Arched back

- Tailpiece attachment to a button by means of a thick gut string

The first reference to a new hybrid instrument combining the physical features of the pardessus and violin appear in 1730 in the inventory of viol-maker Claude Pierray.

Quintons were made all over France with makers in Paris producing the most elaborate ones. They were also built and played in England, Germany and even Sweden. The popularity enjoyed by the instrument was such that Guersan’s violins and even Cremonese ones were transformed into Quintons.

Quinton d’amour versions also appeared, with sympathetic strings in the fashion of the viola d’amore. Quintons fetched high prices, rivalling the most elaborate pardessus. The earliest known extant quinton, as far as the present stage of research allows us to know, is an instrument made in 1733 by Andrea Castagneri (1696-1747). The last maker to build them seems to have been François Lejeune in the early 1770s and the last reference to the pardessus of any type is in Lejeune’s inventory of 1801.

The five string pardessus did not supersede the 6 string model which continued to be built as late as 1760. This is why, in mid 18c France we find co-existing these two 5 string small viols with different physical features, both being called pardessus de viole and both fulfilling precisely the same musical role. And this is why there is not a single piece of music ascribed to the Quinton. All the repertory can be found under a single heading ‘pardessus de viole à cinq cordes’.”

Michelle Corrette said of the Quinton:

“The quinton has a delightful sound because it possesses the fluted high register of the pardessus de viole and the sonorous bass register of the violin – it sounds much better than an ordinary pardessus, the table being less loaded with strings”.

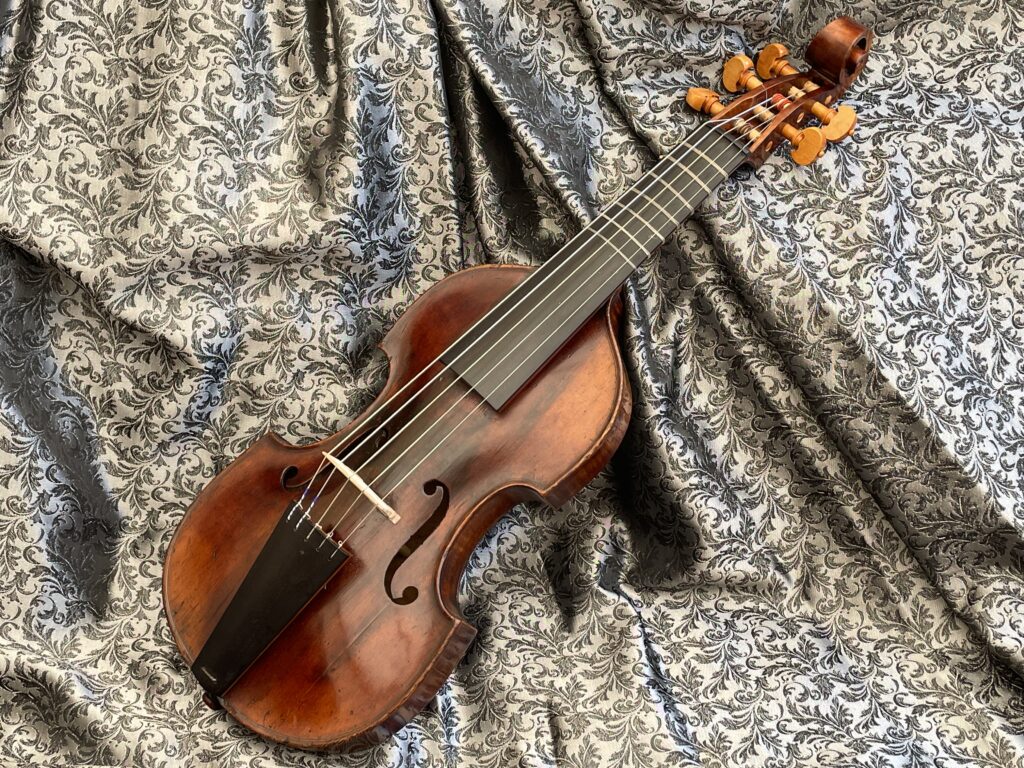

The Viola da Gamba

Large viol with 7 strings is called Bass Viol or Viola da Gamba

The Collichon family of instrument makers were prominent in Parisian musical society during the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. Nicolas Collichon was ‘maître faiseur d’instruments de la musique du roi.’ They were know to such luminaries of the viol as Jean Rousseau, who wrote in 1687 in Traité de la Viole:

“When I was learning from Sainte Colombe I was housed with the bonhomme Collichon, luthier, who at that time lived at Rue de la Harpe.”

“We also ought to thank M de Sainte Colombe for having added a seventh string to the viol whose range thereby grew by a fourth. It was he as well who fostered the use in France of strings threaded with silver and he has a continuing passion to find anything that may add perfection to that instrument.”

The earliest surviving seven-string viols are those by Nicolas Collichon’s son, Michel, and the oldest is example is dated 1683. The seven string viol was reliant on the invention of the silver-covered string, which did not emerge until the 1660s.

It is thought there was more solo music for the viol composed in France during the 17 and 18 centuries, than the rest of Europe. Music was composed in suites with varying dance movements, often preceded by a prelude and sometimes a character piece or fantazie.

Marin Marais, born 1656, was the most prolific composer at the time, writing amongst other works 5 books for the bass viol. These books are a cornerstone of repertoire in learning to play the viol, since they contain detailed fingering, bowing and expression. The pieces in the books, are for solo viol, or 2 viols, with continuo. While some are easy, maybe written for Marias’s students, others are clearly intended to display the composer’s own virtuosic technique. Marin Marias was the court composer and violist to Louis XIV for 46 of the 54 years of his reign.

Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe (c. 1640–1690) He was the teacher of Marin Marais and said of him: “There are sometimes pupils who can surpass their masters, but the young Marais will never find one that will surpass him.”

Antoine Forqueray was born in 1671 in Paris, the son of a Gambist and learnt to play the viol. At age 5 he was presented to Louis XIV who was so stuck by the child’s playing, he called him, his ‘little wonder!’ Jean Baptiste Antoine Forqueray, the son of Antoine, was born in 1700 and also appeared, aged 5, before Louis XIV. He was considered the greatest gamba player of all time.

At the time of Forqueray’s appointment to the Sun King, the most renowned viol player at court was Marin Marais, who was famous for his sweet and gentle musical style. Forqueray in contrast became renowned for his dramatic, striking and brash style. According to Hubert Le Blanc Marais played like an angel, and Forqueray like the devil.

Information about the instruments Jacqui plays:

7 string bass: Copy of an instrument after Collichon, by Robert Eyland 2002

5 string quinton: original instrument circa late 18c.

6 string pardessus de viole (with a golden head): copy of an instrument after Betrand, by Dominick Zuchowicz 1982

Information about the instruments Peter plays:

7 string bass viol (with golden head): a copy of an instrument after Bertrand, made by Ingo Muthesius 2007

5 string quinton: copy of an instrument after Salomon, 1753, made by Roger Rose 2016

6 string pardessus de viole: copy of an instrument after Bertrand made Ingo Muthesius 2005

Read more about the history of the viol below.

The Viol

History

Read moreThe violin and viol family developed in parallel from around the same time: viols from around 1492 and violin family around 1530.

In 2002 the Viola da Gamba Society of UK published Louise Jameson’s dissertation on ‘Isabella d’Este’ as a patron of music. We know from this and other research that Isabella d’Este commissioned the first viol in 1493 and was important in the development of the viol from a single sized drone, with either a flat or no bridge, to an instrument with a curved bridge, made in several sizes.

Until this time consort music had always been played by professional musicians, whereas aristocrats sang or played solo instruments. This was the first consort instrument that was acceptable for aristocrats to play and it interesting to note that Alfonso d’Este played in a consort of six viols at his own wedding celebrations in 1502.

The first documentation of viols in England was 1506, so Henry VIII would have known viols at his court. In the Elizabethan age, consort music was popular in England with composers such as William Byrd, John Dowland and Anthony Holborne to name but a few.

One of the best characteristics of the viol is the resonance and when played in groups, called consorts, the instruments blend together. The range of the consort is similar to that of a choir and historically choristers played viols.

The viol in 17th century England

Read more Charles I played the viol and composers such as John Jenkins, William Lawes, Matthew Locke, wrote for viol consort, during his reign. Tobias Hume composed music with characterful titles and for the time, using new techniques for bass viol playing; for example, the original use of Col lengo (playing with the wood of the bow) can be found in some of his pieces.

Charles I played the viol and composers such as John Jenkins, William Lawes, Matthew Locke, wrote for viol consort, during his reign. Tobias Hume composed music with characterful titles and for the time, using new techniques for bass viol playing; for example, the original use of Col lengo (playing with the wood of the bow) can be found in some of his pieces.

After the execution in 1649 of Charles I, his son lived in exile at the French court. This is where he heard the orchestra of 4 and 20 violins and in the Restoration of 1660, King Charles II brought this new fashion back to England.

Some of the composers at this time writing for viol consort were John Jenkins, Matthew Locke and William Lawes. Henry Purcell also composed for the viol consort, and although advanced harmonically, were considered old fashioned in form for the time.

Towards the end of the 17th century, it became common practice to mix violins with a standard viol consort. However, this fashion was not always received favourably. Thomas Mace, writes:

How music is injur’d

For what is more reasonable, than if an artist upon the composition of a piece of music (suppose of 3 or 4 parts). I say it is not reasonable, yea, necessarily reasonable that all those parts should be equally heard?

Then, what injury must it needs be, to have such things played upon instruments, unequally suited or unevenly numbered. This ia a very common piece of inconsiderate practice of the day. But it has been objected, there has been an Harpsichord, or an organ with it, what then? Has not the harpsichord, or organ basses and trebles equally mixed? The disporportions still the same.. The scoulding violins will out top them all.

Now I say, if this in not an injury both to the music, the composer and the compositions let any judicius person judge.

What is the music of parts composed for, if not to be heard?

But I cry mercy, I had almost forgot, it is the fashion!

Sir Francis Drake the viol

Read moreThanks to the research by Dr. Ian Woodfield, we know more about Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe in 1578 and who the musicians were on the voyage and what instruments they played. There were 4 viol players, Simon Wood, Thomas Meckes, Richard Clark and George (surname unknow), who formed a viol consort. They would have also played cornetti and sackbuts in a wind ensemble, known as ‘Lowd musick’. The viol consort was called the ‘Soft or still Consort’. Trumpeters were recruited separately and their band was know appropriately as a ‘noyse of trumpets’. Sea going musicians of all kinds were rarely unoccupied and their regular duties included:

Playing for Sir Francis Drake during meal times.

They signalled loudly during fog to precent other ships from crashing into their vessel.

They accompanied the psalms sung at the daily service on deck.

They played songs and dance music to entertain the crew during the long voyage.

However, it was the soft consort of viol players that were rowed out to shore with Drake, to perform music, therefore demonstrating their peaceful intentions.

Comparing the viol and violin families

Read moreThe violin family, known as viola da braccia and played on the arm, and the viol family also known as viola da gamba, which are played on the knee, are two different string families that co-existed from around the end of the 15c. (It’s a common myth that viols preceded the violin family!)

We know from orchestral instruments we see today, that violins, violas and cellos are well known, but the family of viols, whose repertoire was long established before that of the violin family, is still relatively unknown.

If we compare the viol to the violin, we have :

| Violin family | Viol family |

| F sound holes | C sound holes |

| Narrow ribs | Deep ribs |

| Scroll | Carved head or scroll |

| Unfretted fingerboard | Fretted fingerboard |

| Front of instrument protrudes over the rib | Front and ribs joined at right angles |

| Curved back | Flat back |

Viols are perfectly suited to the spaces for which they were originally intended to be played; in country houses and at the Royal Court. It is the resonance of the viol which makes it such a special instrument to play in a group or consort. The lighter construction; strings with less tension than the violin; frets (so that notes can be held down for longer) are contributing factors to the resonance.

Frets

Read moreThe role of the fret on the viol is to make each note like an open string, making the sound very pure. Frets make viols easier to play because they help with finger spacing and intonation. Players can hold fingers down, keeping the sound ringing; adding fingers on the same fret is standard practice, rather than jumping string with the same finger.

Tying, tuning and setting temperaments with frets by adjusting the position of the fret gut on the fingerboard is also standard practice for viol players.

The underhand bow hold and principles of bowing by Jean-Baptiste Forqueray

Read moreAll viols are usually played with an underhand bow hold, where the bow hair is in contact with the middle finger. This enables the player to tension the bow hair to create a range of dynamics without changing the bow speed.

Jean-Baptiste Forqueray considered the bowing arm to be the key to making a beautiful sound. This is an extract from the letter mentioned above to Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia in which he explains:

“It should express all the passions: it is the bow that stirs the soul; finally, it is the bow that gives the character of all types of music. To have this beautiful bow, I find there are four principles:

The first is the position of the arm, which should extend from the shoulder to the wrist, having the arm stretched without stiffness, and which should be supple both when pushing and pulling.

The second principle: that the bow always moves in an horizontal line on the strings. That the tip of the bow never varies, that is to say neither rising nor lowering, and is always opposite the thumb.

The third principle: that the bow never leaves this line and is three fingers from the bridge and well balanced, and above all that the wrist moves outwards in pushing and inward in pulling. In performance, it is the wrist that moves and not the arm, it should be suspended and very supple in moments of great virtuosity.

The fourth principle: it is the use of the second finger on the bow (the middle finger) which is the prime means of expression, and which gives character to the music. For this, it is necessary that the bow hair is placed at a cross with the joint of the second finger, and that it never leaves this position (see above). This finger presses the hair against the string to make more or less sound; by pressing and relaxing it imperceptibly it makes the expression, the soft or loud. Above all one must observe, Monseigneur, that the bow thumb is placed lightly on the wood. It if is pressed too hard, it gives much harshness to the performance and crushes the bow on the string – this one must absolutely avoid.”

Extract from Forqueray’s Pièces de Viole (1747): A Rich Source of Mid-Eighteenth-Century French String Technique by Lucy Robinson.

What sort of music is played in a viol consort?

Read moreDance music, such as Pavans and Galliard with improvised divisions, (you could call ‘Tudor Jazz!)’ as well as Fantasias, In nomines, Consort songs, verse anthems with voices. The musical style for the Fantasia is polyphony and this means all parts have the same or similar themes played in horizontal lines.

Contemporary music also has a place with viols as some composers like a pure, non vibrato sound. For example, composer Terry Davies specifically requested viols for his score for the production of Romeo and Juliet at the RSC in 2003.

The standard combinations for viols for 17th century English music was set out by Thomas Mace in his book Music’s Monument in 1676:

‘Your best provision and most compleat, will be a good chest of viols: six in number; viz, 2 basses, 2 tenors and 2 trebles; All truly and proportionably suited.

Why have most people not heard of a viol?

Read moreOne reason was when the performance of music went into larger, public spaces such as theatres, from country houses, the viol’s lack of projection meant that the louder violin family became more popular and fashionable. So today, there are no viols in orchestras, as they are used usually primarily for playing in small groups, called consorts.

Sources

A Question of Wood: Michel Collichon’s 1683 Seven-String Viol by Shem Mackey, Journal of the VdgsA Volume 47, 2012.

‘Is the Quinton a Viol? The Puzzle unravelled, by Myrna Herzog, Journal of the VdgsA Vol 40, 2003.

‘Re-examining the pardessus de viole and its literature, Part 1, Introduction and Methods’ Richard Sutcliffe, Volume 37, Journal of the VdgsA, 2000.

‘The pardessus de viole’ – Notes for a Maters Thesis by Adrian Rose 1995.

‘The pardessus de viole and its literature.’ Early Music. Early Music America. 10 (3): 301–307 Green, Robert (1982). J.M. Thomson (ed.).